Daughter Tamara Leiokanoe Moan and granddaughter Juliet Keolaokeao Moan-Johnston lead the procession of program presenters. Following them are cousins Jenny Jacky, Kealakai, Kāheale’a and Kāheaikamelekai Roska, and my son, Rolf Kaleohanohano Moan.

Aloha no ‘oukou. I wrote the Aloha poem in your program in 2020 for my holiday card that year, as a gift from me to you. I have lately realized that it can also be a gift from you to someone else. I hope you will use it that way. Please join me now in reading it aloud together. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my Grandma Monkey for her continued support of me throughout my life. She has always been there to answer my questions and encourage my endeavors and teach me lifelong lessons. I still remember the sewing lesson that I received at the age of five or six when we made a small doll with a pink dress and blonde braid. That experience led me to discover my love of sewing.And I would be remiss if I failed to mention the very educational lessons Grandma Monkey gave me on how to scare one leaving the restroom.Cousin Kāheaikamelekai Roska dances “Pua Hone.” Son Rolf and I are watching, along with everyone else.

Guests had several moments of group laughter during Rolf’s speech. They came from Oregon, Alaska, Minnesota, Virginia and Aotearoa as well as from Hawaii Nei.

Over the years, my sister Tamara and I have realized that we’re drawn to people who have an unusual combination of traits—on the one hand, these are people who are tremendously responsible, thoughtful, sensitive; they care deeply about the world and about their place in it. On the other hand, these same people have a silly, eccentric, and somewhat unhinged side. This combination describes many of the mentors, the friends, and of course the spouses we have chosen to spend our time with.And it took me a while, but I finally realized one day “Of course! This combination perfectly describes my mother! Aha!” On the one hand, Sally-Jo is a woman of great depth and great accomplishments. She has a gift for organization, she’s an extremely talented singer-songwriter and visual artist, and she is a marvelous journalist, essayist, poet, and fiction writer. She’s published over 200 articles in some 50 magazines, has won at least 17 different writing awards spread across a variety of genres, and she has published two books, including one of my all time favorites—The Heart of Being Hawaiian, which is a collection of articles and essays about Native Hawaiian history and cultural traditions and about her own experiences as a Native Hawaiian woman. She also wrote a 480-page genealogy of the Pa family that she has shared with many of us—which is a great resource and a fun read. I’d say that Sally-Jo qualifies as a “kahu”—a keeper of bones, a guardian and protector and caretaker of meaningful traditions and values, someone of deep commitment and responsibility. At the same time, she is also the very opposite of serious and responsible. In fact, she regularly exhibits characteristics that can only be described as troubling, alarming, and semi-criminal. I thought I’d give you a few examples. Although Sally-Jo is deeply respectful of others and of different cultural traditions, she has a contrary side also: She often refers to herself as “Toad”—that’s right, “Toad” (as in “It is I, Toad,” which she often says when she answers my phone calls)—a practice that many amphibians, I would guess, would view as a form of inappropriate biological appropriation. Sally-Jo also went through a phase in which she would call the Oregon Department of Justice, where I work as a lawyer, and ask to speak to me while identifying herself as “Hwang” and using what she apparently considers a passable “Chinese” accent. I once picked up my work phone and our receptionist said, “Rolf, there’s a Mr. ‘Hwang’ calling for you? I had trouble understanding him,” she said. “He has a very heavy accent.”Which reminds me: During my first couple years as a lawyer at the Oregon Department of Justice, my mother presented me with a gift that she had made by hand and she suggested that I hang it on my office wall. She called it a “goof gas gun.” It kind of looked like a rifle: It was made out of a long cardboard cylinder, the kind that comes inside a roll of wrapping paper, and had an ornately decorate dcardboard stock and trigger guard, and featured lots of curlicues. Feeling like I had no choice, I went ahead and hung it prominently on my office wall. My boss wandered by not long after and said “What is that?” I said, “It’s my goof gas gun! My mother made it for me!” My boss gave it a closer look, nodded his head, and said “Ahh!” as if the item explained quite a bit about me, and moved on. Finally, Sally-Jo has a semi-criminal stalker-ish side. She loves nothing more than lurking outside a bathroom while you’re inside taking care of business, and then yelling “Boo!” and lunging at you when you emerge. Sadly, she has successfully taught her granddaughter Juliet to do the same thing. Sally-Jo once lurked outside the women’s room in a fancy restaurant in Ft. William, Scotland, while Tamara was inside. She failed to take into account the fact that this was nota single-occupancy restroom but instead was a shared space. When the women’s room door opened, Sally-Jo was in mid-lunge when it became apparent that the woman emerging from the room was not Tamara but instead was an unsuspecting middle-aged fellow diner. Fortunately, the woman was so taken aback and disoriented by the experience that we managed to pay our bill and leave before the authorities could be called.So as we celebrate Sally-Jo today, I think it’s important to celebrate and appreciate not just her responsible and accomplished side but her all-too-human wackadoodle side also. And if you use the facilities today, I would suggest that you use the “buddy system” to ensure your own safety, especially if you see Sally-Jo and Juliet huddled together and staring at you as you enter the facilities. Thank you.O Kealakai ko’u inoa. My name is Kealakai. It means “Pathway of the Sea.” Last year my name meant that I had a strong connection to the ocean. Although it still means that, here are a couple of new meanings of my name: 1. Pathways. I believe my name also means I can always find the right path even if it’s not the one expected of me or even if I have to pave it myself.2. Courage. I also believe my name has a connection to the people who first found the pathway of the sea and found Hawai’i. I will try to aspire to their great courage!3. And most importantly mahalo nui to Aunty for my name.•••••••••••••••••O Kaheale’a ko’u inoa. My name is Kaheale’a, which mean “Calling Joyfully.” Before I was born, my parents struggled with infertility. So, when I was born, I was a joy to them and our ‘ohana. I came out in full voice, which is also part of the reason I was named Kaheale’a. When I first understood my name in my own way, I thought about the joyful part—because my new school came with lots of new and true friends. Today, I think of my name as the whole. Partially because in the past year, I have seen myself call out or reach out to others in a joyful way. I also feel myself being more confident in myself and in my friendships. In the future, I want to continue to reach out to people in a joyful way. But, I also want to call out when I see something wrong or unfair—to help move more toward a joyful environment for all. Thank you, Auntie, for the beautiful name and happy 85th birthday•••••••••••••••••

Aloha pumehana kakou. O Kaheaikamelekai ko’u inoa. My name is Kaheaikamelekai.

There is so much I want to say about Aunty, but I am going to try to keep it focused. Aunty Anuenue is my Tutu Mailelani’s first cousin. Aunty and I first corresponded when I was in high school because I wanted to be a writer. We were pen pals starting in the 1990s and then became travel companions and now fast forward 30 years, she refers to me as her honorary daughter. It’s both mysterious and strange and a perfectly natural relationship.

In 2006, when aunty was taking a trip to Hawai’i, she asked if I wanted anything. I think she meant guava jam or macadamia nuts. But instead, I said to Aunty: “Would it be appropriate to ask for a Hawaiian name?”. She graciously said yes. In 2007, she named me, or as aunty would say, she received a name for me.

She received the name from the Spirits and the ancestors and then I received the name, Aunty gave me one of the most sacred gifts I have ever received. I live in what is now Minnesota, land of the Ojibwe and Dakota peoples. In Ojibwe, there is a word: niiyawen'enh. It is the word for a naming ceremony and also the word for the person facilitating the naming ceremony. Niiya, means “my body.” The idea is that when you are giving someone a name or receiving a name, there is a physical reality to it. You’re basically gifting someone a part of your soul, which will then reside in that other person’s body.

This Ojibwe concept helps me better understand the depth of gift Aunty gave me. When you give someone a name, you're giving them part of your soul. And when you accept a name, you're both accepting the soul given and you're giving part of your own. The process of naming and being named is profound and deep.

I have tried to hold my name with that kind of reverence—in order to honor the fact that aunty gifted me part of her soul when she named me. I have a responsibility to honor that gift.

The name I was given Kaheaikamelekai means called by the song of the sea. There is so much to say about the kaona of my name that has continued to reveal itself over time but I will just focus on one aspect: I am known as Kahea, for short. Called. Some of my family and my hula group call me Kahea.. Every time someone says my name, they are saying called. I am called. As I believe every person is. But I just get reminded of it every time someone says my name. I think a person’s call as a Kuleana. It’s a divine invitation, a divine responsibility to listening to the Spirit, understanding who your ancestors are, learning from the aina and listening to those in your life you trust most.

I think one of greatest gifts that Aunty gave me was her transparency about not feeling confident that she was equipped to do the job of naming. And yet being willing to try anyway.

That lesson stayed with me because about two years before my mom died, my mother asked me if I would give her a Hawaiian name. My mom’s birth name was Lani, but she wanted a longer Hawaiian name, perhaps as a way of affirming her connection to her Hawaiian heritage—which she had felt disconnected from. At first I was taken aback by my mother’s request. I asked Aunty about whether it was pono to name my own mother, assuming she would say no. I was actually hoping she would say no.

But we talked about it, and she said that first of all, you want to honor a request like that if you can. And secondly—that in terms of knowledge about Hawaiian language and culture, I was kind of an elder to my mother. In no way did I feel like an elder and I did not feel equipped for the task, but I listened to Aunty describe her naming process and I spent a lot of time with my Hawaiian dictionary and in silence. When the name finally emerged, I was hapai with my oldest daughter. So, at that time in my life, I had named dolls and dogs. I had never named another human being. I had the chance to name my mother before I named my daughter.

This part is a little tender to talk about—the name that emerged was Mohalakalani. Mohala means to unfold, open up, blossom, evolve, recover. At the time, my parents had recently divorced. I thought I was giving my mother a name that meant she was blossoming into her full self. But my mom died about 18 months after I named her. There is no way I could have known that she was unfolding toward heaven/the sky in a much different way. This is the thing about kaona. It has a life of its own.

Aunty also received Hawaiian names for our two daughters. Tim and I have tried to practice that level of care with each of the other names we have chosen for our children.

Aunty has given me a part of her soul, and she has seen things in me that I did not see in myself. By articulating her own insecurity about not feeling Hawaiian enough, she gave me permission to authentically claim this part of my heritage. I am many other things, but I am also Kanaka Maoli.

Aunty has given me many gifts. Including my name. But I think her biggest gift is being her authentic self, which has helped me continue to live into my authentic self. That is indeed a gift that I carry around physically in my soul.

Cousin Jenny Larson Jacky and daughter Tamara Leiokanoe Moan dance “Hanohano Wailea.”

In 1972, I met Sally-Jo Moan, as she was known in those days, when I worked as program director for the Northwest Outward Bound School in Eugene, Oregon. She participated in one of the programs, then joined the staff to handle advertising and public relations.

A 1920s book called “Woodcraft” had circulated through our field instructors. The author, a woodsman or Mountain Man, writes about camping and camp gear. The book’s lessons were not a whole lot different than what I was teaching the staff. So they started calling me “Old Woodsman” or “OW” for short.

Sally-Jo later told me that, as she got to know the field staff and heard reference of me, she was hesitant to work too close to me as woodsmen smell bad, don’t they?

That fall I took most of a month off to deer hunt. While I was away I invited Sally-Jo to use my office as she didn’t yet have a space of her own. My desk top was covered by an old-fashioned calendar/blotter—just the kind of thing you would not want to spill a cup of cocoa on. But shit happens. Sally-Jo, or SJ as I called her, tried to find a replacement blotter to no avail. I did receive an apology, however.

As I was in charge of the programs and Sally-Jo was supposed to promote them, we worked pretty closely together. In addition, she wrote our first staff manual and put together a book of inspirational writings and poems. We had lots of time to discuss life and other important matters like: I am a guy from the sticks and found this Women’s Lib thing confusing. I mean why would you want to burn a perfectly good bra? Sally-Jo kindly enlightened me. I was reciprocal, in that I shared boating and woodcraft skills. And maybe some stories about the old guys in Blue River, Oregon (where I grew up) and elsewhere who steered me in the right direction.

When we came to live together, I sent a letter of introduction to Ida May, Sally-Jo’s mother. Somewhere in the text I told Ida May that in addition to SJ, I called her Sassy as that was the way I found her, me not understanding assertiveness. Her mother told me later that Sally-Jo was always like that.

We left Outward Bound together to work back-country trail-building jobs, leading work crews of high school kids. We made a good team, my woodsman skills and SJ’s organizational expertise. Over several years we worked in Washington’s North Cascades, Yellowstone National Park, and the Olympic Peninsula. I also led outdoor trips for the Eugene Parks Department with SJ as my second.

At some point I began to address her as “Pretty Lady” or “PL,” which totally confused the jeweler when we told him to inscribe the inside of our wedding bands “To PL from OW” or the other way around. “Whose initials are they?” he asked.

SJ is a Sassy, Pretty Lady still. And this OW has shared many mountain tops, many river canyons, some hot deserts, and some cold snowshoe trails with her. Meanwhile, this OW has received enlightenment, as it were, while being introduced to theater, fine arts and some not so fine. I have been read bed time stories and received my first stuffed animal—Ted D Bear—from SJ.

The mountains have become too steep. Some of the theater has become difficult to hear. We shouldn’t eat raw onions any more. And we each have two or more pair of glasses. But our love and devotion to each other has not changed. So friends and family, I ask you to celebrate this remarkable woman. She has touched you all. And while this Pretty Lady has slugged this Old Woodsman a time or two, I am better for it.

Sometimes I have to escape alone to the mountains, or to a river. But at those times, I often hum a rock-and-roll tune of our youth: “To Know Her Is to Love Her.” And you knew that even without me telling you.

Thank you. – David WalpDid someone start in the wrong key? Or is there another reason for hilarity? Left to right: cousin Georgia McMillen, friend Bill Rezentes, myself, cousin Anuhea Reimann-Giegerl.

When I was a kid, my mom introduced us to the wonderland of Kailua. Kailua for me included the smell of flower lei that covered us once we stepped off the plane, it was the salt smell of the ocean as we walked down the beach path, it was our grandparents and their house as 156-B North Kalaheo. The family footprints marked the cement floor of the carport. There the hau tree shaded a table where the grownups told stories. We loved to climb the hau’s knobby trunk and poke our heads out the top of the tree to spy on the neighbors’ from above the leaves. Back when my mom was a kid, Kailua’s roads were still crushed coral, the cartoons and feature movie on Saturday morning cost 15 cents, and Honolulu was far away.

Sally-Jo spent small kid time in Kailua but also spent chunks of time in Fargo, North Dakota to visit her mother’s family. She made a trip there with her mother in November 1941—and got stranded on the mainland until February 1943. Ida May, Sally-Jo and her little brother Peter traveled to Fargo again from April to October 1946, as soon as the travel bans were lifted after the war. On other trips during the ‘40s and ‘50s, Sally-Jo spent all of third grade and parts of fifth and sixth grades there. She learned to roller skate and ice skate in Fargo and built a lot of snowmen.

Back in Hawaii, she began seventh grade at Kamehameha Schools as a boarding student. She excelled at academics and her journalism career got its start there. She forged lifelong friendships with other girls who boarded. Decades later I always enjoyed tagging along with my mom and her classmates. They morphed back into silly, giggling 13-year-old girls when the stories and memories started to flow.

Sally-Jo returned to the Midwest to attend college. She met my dad at the University of Minnesota; they got married and later moved to the west coast. Although my brother and I were raised in Oregon, our mother sprinkled our life with island stuff. She shared family stories, Hawaiian legends, foods, and words like piko and pau. Our visits to Kailua connected us to a vast and wonderful Bowman `ohana, local music, hula, island happenings like a pidgin production of Shakespeare, and of course all things ocean.

My mom grew up in the 1940s and ‘50s, a time when it was uncool to be Hawaiian. I grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s, a time when the Hawaiian Renaissance reawakened Hawaiian pride. Although we lived in the Pacific Northwest, our mother was paying attention. She shared the thirst for reconnection. While my brother and I were in high school and our mother worked in the University of Oregon’s publication department, she began a master’s program in journalism. She wrote her thesis on the Hawaiian Renaissance, digging into the changing culture with a reporter’s curiosity that also fed a personal journey. Later as a freelance magazine writer, she continued to write about Hawaiian issues as a way of educating herself and forging connections and friendships in addition to earning a living. She still maintains close ties with many of her interview subjects, some of whom are here today.

Writing about Hawaiians and Hawaiian culture helped my mother identify and claim the Hawaiian parts of herself. She came to new understandings of Hawaiian concepts like kuleana, `aumakua, and native knowledge of the natural world, the mind-body-spirit connection, and a learning style based on observation and doing. In 2008, Watermark Publishing issued The Heart of Being Hawaiian, a collection of her Hawaiian-centric magazine pieces. The popularity of the book shows she struck a chord with others looking for their cultural identity.

Watching my mother explore her Hawaiian heritage through her writing has been a model for me. I moved to Hawaii in 1987 when I was 25. I didn’t feel local but I didn’t feel like a malihini either. Over time I dipped into lots of Hawaiian cultural activities—surfing, paddling, hula, lauhala weaving—and studied history and `olelo Hawaii. But it’s really been through writing about my experiences in recent years that I’ve come to a deeper understanding of who I am as a Hawaiian, my Hawaiian values, and my personal kuleana.

Today I live five doors down from the house where my mother grew up, on that same small beach lane off North Kalaheo Avenue. Kailua Town is a busier place, more visited by tourists. The beach is a constant, but its width has shrunk and the rising sea no longer leaves dry sand exposed below Lanikai Point at low tide. The houses on the beach lane are owned now by retirees and snowbirds, not families with children.

Yet much remains. The salt sea smell still greets you at the top of the beach path. Iwa birds soar overhead at dawn. The water beckons. Memories and family surround me. My mother imparted her love of the water to us and I am in the ocean as often as possible. I think it is one of the things she misses most living in the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Now it’s my turn to share Kailua with her. I give her the neighborhood gossip and send her newspaper clippings every week on island stuff. When we talk, I often give her the ocean report and note when conditions would be perfect for her. These days when she’s in Kailua and we go into the ocean together, I insist on being her safety officer, there to help her through the surf and over the puka-filled floor. Past the breakers we float free, beyond the pull of achy joints, tired muscles, headaches, or aggravation. It is just ocean and us..As is the custom, a group gathered for a Hawaii program or purpose holds hands to sing “Hawaii Aloha,” the 19th century hymn that has nearly replaced Hawaii’s National Anthem as a unifying song.

The food service crew, left to right: David and Oliva Wise and son Christopher (far right), grandniece Isabelle Bowman and her parents, Sam and Anne Bowman. The Wise family also oversaw and engineered setting up tents, tables and chairs, arranged neighborhood parking, obtained various supplies, and made and ordered various lei.

In the wild majesty that dominates this part of Windward O’ahu where I grew up, the Ko’olaupoko mountains comprise one of Hawaii’s “wahi pana,” or legendary places.

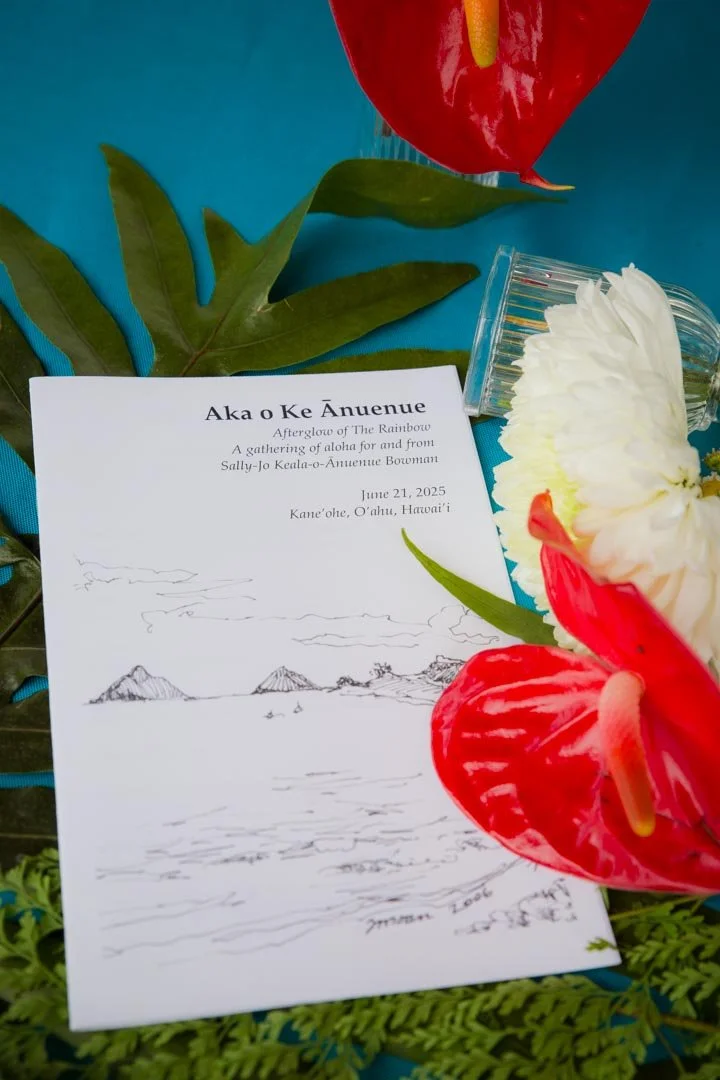

Cousin David Wise blows the pū, the shell trumpet, announcing the opening of Aka o Ke Ānuenue. The pū was made by my Kamehameha Schools classmate Gordon Lee. David’s home is the site of today’s event.

Leading guests in chanting “E Hō Mai” are, left to right, Kealakai Roska, Tamara Leiokanoe Moan, Kāheaikamelekai Roska and Kāheale’a Roska.

My son-in-law Steve Katz and nephew Sam Ku’ikahi Bowman join guests in reading aloud my poem “Aloha.”

Granddaughter Juliet Keolaokeao Moan-Johnston presents me with a special pikake lei. In 1931, my Aunty Nina Bowman adorned her wedding gown with several double-length strands of pikake. In the mid-1950s Nina bought the property that is the site of today’s event and now belongs to her grandson David Wise and his family.

Son Rolf Kaleohanohano Moan gave his own talk as well as that of my husband, David Walp, who could not attend. Rolf also had the role of kahu for the event.

Kealakai Roska giving her speech using a microphone for the first time. She is age 9.

Kāheale’a Roska giving her speech. She is 11.

Cousin Kāheaikamelekai Roska bestows a hug at a very touching moment.

Tamara Leiokanoe Moan dances the signature hula of Halau Mohala ‘Ilima.

Bill Rezentes chanting, with ‘ukulele as percussion.

Catered Island menu included kalua pig, rice, lomi salmon, chicken long rice, Okinawan sweet potato, garlic chicken, lilikoi tossed salad and haupia.